William Shakespeare Hall

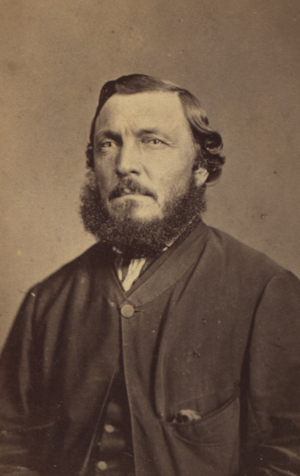

Portrait taken c. 1870

| |

| Birth: | 1825 |

|---|---|

| Death: | 1895 |

| Parents: | Sarah Theodosia Hall (née Branson) 1793 – 17 February 1858 Henry Edward Hall 1790–1859 |

| Siblings: | Laetitia Hester (née Hall) 1822–1877 William Shakespeare Hall 1825 – 1895 Theodosia Sophia Hester (née Hall) 1827–1898 James Anderton Hall 1829–1888 Edward Frank Hall 1832–1886 Sarah Louisa Bracher (née Hall) b. 1819, England; d. 1910, Victoria, Australia Henry Hastings Hall c1812–1879 |

| Partners: | Hannah Boyd Hall (née Lazenby) 1849–1911 |

| Children: | Henry Ernest Hall 1869–1941 Harold Aubrey Hall 1871–1963 Joy Hannah Emma Margaret Clifton (née Hall) 1876–1960 William Shakespeare Hall Jr. died in infancy, Cossack, 1878 Grace Hall died in infancy, 1875 |

| Keywords: | H.M. Wilson Archives |

| Authority control |

Permalink: archives.org.au/WSH Wikidata: Q8018316 Wikitree: Hall-22337 WABI: IJ/IJ2162 FamilySearch: LZW7-5LZ Ancestry: 312115279515 |

Please see the following Wikipedia article for more coverage of this topic:

William Shakespeare Hall

From The Building of Jarmen Island Lighthouse, 1888 (published 1936):

“Shakey” Hall had a quarrel with another well-known settler named Fauntleroy, who did not take it seriously. However, when his dog had pups he named them all after the members of “Shakey’s” family—“William Shakespeare,” “Hannah,” “Aubrey,” “Ernest” and “Joy.” Everyone treated this as a joke, and took a delight in addressing each of these pups by their respective names. During Faumrtleroy’s life-time, “Shakey” was ignorant of this joke which Fauntleroy had played on him. After his death, he learned of it and waxed very wroth, declaring he would go to Roebourne, where Fauntleroy was buried, and defile his grave. Needless to say he never did.

Poor old “Shakey” came to an untimely end some years later. He was very fond of sea bathing and a strong swimmer. Early every morning, summer and winter, into the creek opposite his house he went. He was found face downwards in three feet of water, quite dead, evidently heart failure.

DAAO biography

His biography from Design and Art Australia Online:[1]

Sketcher, explorer, pastoralist and pearler, was born in England on Christmas Day 1825, second son of Henry Edward Hall and Sarah Theodosia, née Branson. He came to Western Australia with his parents, two brothers and three sisters in the Protector , arriving at Fremantle on 26 February 1830. He attended Rev. J.B. Wittenoom's school at Fremantle and his earliest known sketch, dated 15 December 1843, is annotated Chaplain J.B. Wittenoom’s Residence. In 1852-60 Hall was at the Victorian goldfields. On his return, he joined Francis Gregory’s exploring party to the north-west of Western Australia. Two years later, he took up Andover, the first sheep station in the Roebourne district, on behalf of John Wellard. He explored the Fitzroy River with McRae in 1865. Hall’s surviving diaries for this period (1861 and 1863-64) give details of his life but make no mention of drawing.

Few works are known but Hall continued to sketch until at least the late 1860s; Roebuck Bay Station is dated 7 October 1866. Other pencil drawings such as Mesas South of Carnarvon are undated. In 1869 Hall became a storekeeper, shipowner and pearler at Roebourne and was involved in the establishment of the pearling industry at Broome. He died of a heart attack while swimming in Cossack Creek on the evening of 11 February 1895. He was survived by his wife, Hannah Boyd, née Lazenby, whom he had married on 2 November 1868, and three of their four children. His papers are in the Battye Library, Perth, WA, but his sketches are still privately owned.

Two children lost

From History of Western Australia by W. B. Kimberley, Chapter 11 (p. 100). The children are presumed to be William Shakespeare Hall and James Anderton Hall.

On the 11th December, 1834, two children of Mr. Hall, on the Murray, went down to the sea-beach to watch some soldiers fishing. One returned home soon after noon, but the other lost his way in the bush. At four o'clock next morning Mr. Norcott, accompanied by two white men and the natives Migo and Mollydobbin, who were attached to the mounted police corps, went out in search of the child. They soon came upon his track along the beach to the northward. The Europeans were quickly nonplussed, for a fresh wind had covered up the track with sand. Not so the natives. Their practised eyes traced the boy's wanderings four miles along the beach, when they intimated that he had turned into the bush. They followed his movements with astonishing minuteness, and led the way into an almost impenetrable thicket, through which they had to crawl on hands and knees. Loose shifting sand lay on the clear spots amid the bush, and thus their task was fraught with the utmost difficulty.

After about an hour's time the beach was regained, for the boy had only made a circuit inland of 400 yards. There the track was again distinct, and for five more miles, with occasional turnings in and out of the bush, they traced the erratic steps of the poor lad. Eventually even the natives were momentarily at fault, for the boy had entered another thicket which it was almost impossible for them to penetrate. But presently they cried out "me meyal geena," meaning "I see the footmarks." Their progress was now watched with the intensest interest by the white men, who viewed with ever-increasing amazement their acute perception. Through a dense mass of matted bush they forced their curious way, and when Mr. Norcott began to despair of success, the natives inspired his confidence by holding up a cap which was known to belong to the child. Again the track led along the beach until some sand cliffs were reached, where the wanderer had gone to an elevated spot. The wind had entirely effaced all marks of his feet in the loose sand, and it was an anxious moment for the search party. Migo was not daunted. Descending the hill, he persisted in making a circuit at its base, and after a little time he fell in with the track. But even here sand had obliterated most of the footsteps, and for nearly two hours the natives alternately lost and refound them. The party had nearly given up all hope of recovering the child when Mollydobbin saw a track on the side of a deep ravine. The natives went down into the ravine and commenced hallooing, hoping that the child might be asleep in the bush. Next they had to penetrate bushes and thickets more dense than any previous ones, and once again they emerged on the beach. Observing by the tracks that the child had been there but recently they pushed on with great eagerness, and at a distance of about 300 yards were delighted and gratified to observe the boy lying asleep on the beach, his legs idly washed by the surf. Another hour and probably the child would have perished, for the tide was rapidly coming in. Mr. Norcott galloped up to him, and calling him by name, the boy awoke and instantly jumped up.

The joy and delight of the two natives are said to have been beyond description. They had walked for nearly twenty-two miles with their eyes constantly fixed on the ground for ten consecutive hours, and they evinced such great anxiety as to the little one's fate that Mr. Norcott says he could not but applaud the noble disposition of these two savages.

References

- ↑ William Shakespeare Hall b. 25 December 1825 Artist (Draughtsman), Design and Art Australia Online. Date written: 1992. Last updated: 2011.

Items

· Homepage · Tree · Photos · Archive items · Military service · Graves · Storage locations · Private archives ·